Samir M'kadmi

Norway-based, French-raised, Tunisian-born artist Samir M’kadmi is perhaps the only man international and open-minded enough to have curated the trash art show, seminar and catalog “Recycling the Looking Glass“. As you are well aware by now, due to my constant raving since returning, the show opening was a huge success. Despite the demands of a crazy schedule putting on international exhibitions and keeping up with work of his own, Samir kindly agreed to provide everydaytrash readers with a bit more depth on the making of the Oslo show and where trash art falls in the art historical cannon.

—

everydaytrash: How did the concept for “Recycling the Looking Glass” come about?

M’kadmi : “Recycling the looking-glass” is a result of research and interrogations on topics related to contemporary art, our environment, and global society. Through “Recycling the looking-glass” I tried to re-conceptualise crucial interrogations of globalisation, environmental and cultural issues by resituating these topics not only at an aesthetic level, but also by interrogating and exposing their ethical dimension. These interrogations also occupy a major place in our Norwegian media debates. Of course, these kinds of topics are not specific to Norway. They are global. But, the way these issues are addressed, in Europe, Scandinavia and specifically here in Norway, through our major media, is quite disturbing.

In fact, we can summarise the debate in a few terms: Islamophobia, racism, poverty, immigration, war and terrorism, climate and environmental changes. The first six topics relate to globalisation, cultural and geopolitical domination matters, where concepts such as cleanliness and purity are very often used as metaphors for “our” Western culture and values, and uncleanliness and impurity as metaphors for the “other’s” culture and values. Although this point of view does not reflect the opinion of the majority of Norwegians, it does reflects the opinion of about 17.5 percent of Norwegian voters, which approximately corresponds with the number of voters for the Progress Party (the extreme right).

This point of view, the “other” perceived as a threat, as impurity, as trash, seems also to be the only means of access into the media debate. This is a debate initiated and defined by the editors of the major national newspapers, such as the conservative Aftenposten.

Climate and the environment are tightly linked to the first topics. Here again, the interrogation seems to be blocked between two points of views, one that supports the UN Climate Report and another that opposes it. Here again we find the same political constellation. On the one hand, we have the extreme right, (the Progress Party), which tends to reduce the climate report to a big hoax, on the other hand we find the other political parties who swear by the report and propose some cosmetic environmental solutions. The aim of this debate is how to reduce the discharge of toxic emissions. In short, waste, as toxic emissions, as household or industrial trash, seems to be a common denominator for globalisation, climate change, environmental, and cultural issues. How do contemporary artists deal with these questions? Do they deal with these questions at all? What can artists tell us about trash, recycling, reducing and reusing? Does trash or decay have any aesthetic value? What is the relationship between archiving and trashing? These are just a few of the questions that contributed to the elaboration of the concept behind “Recycling the looking-glass”.

Artist Jan Franciscus de Gier discusses the Euro pallets he and partner Vigdis Haugtrø contributed to the show with a Nowegian artist attending the opening

everydaytrash: How did you select the participating artists?

M’kadmi : Selecting the artists for “Recycling the looking-glass” was tightly bound to the development of the exhibition concept itself. It is a work in progress, and a complicated process because it demands a lot of research, especially if you want to articulate simultaneously different approaches and practices in the same context. Every artist represents a unique and at the same time complex position. When you present artworks made by different artists, side by side, you create not only an opportunity to investigate the artworks, and question the artists behind them, you also provide an occasion to confront your own presuppositions and ideas on art, trash and society.

everydaytrash: One question raised at the seminar was what is the line between art and politics and is there a definable border. What do you think?

M’kadmi : I consider the artist to be an intellectual and a political subject. There is no line between art and life. Art is life, art is science, art is philosophy, art is poetry, and art is politics… The French philosopher Jacques Ranciere describes the political subject, among other things, as a non-static entity and a vector of change. He or she only exists through their actions, through their capacity to change the given landscape, to make visible, to show what was hidden or not perceivable. The political subject opens up the political field through his/her activities, beyond the parameters of all known and accepted political institutions.

We are, everywhere, confronted by interests and ideologies that tend to reduce the artist only to a producer of commodities, rejecting any thoughts and ideas that are not compatible with the idea of the artwork as an open creation, and the idea of the work of art as an object. Utility value is, and has always been, a key theme in an art context, in particular if one eradicates the distinction between the ethical and the aesthetic, as did e.g. Marcel Duchamp with his Fountain in 1917. I situate art’s utility value in its freedom and independence, in its autonomy. In short, the political subject exists as the effective manifestation of the capacity of anyone to personally engage in common affairs.

Duchamp's "Fountain"

everydaytrash: What is the connection between found object and trash art?

M’kadmi : Trash art is an art form that insists on a status as waste. Found objects on the other hand, cling tightly to the identity of the object. Found objects are, as the name indicates, a found object, “un objet trouvé”. It is an object that has retained its integrity but has been removed from its original context.

Schwitters' "Cherry Picture"

Dadaism and the Surrealists attacked High Art by introducing elements from reality in their works. Kurt Schwitters created art from “ détritus”, “l’art du détritus”. Marcel Duchamp’s readymade gave another dimension to “L’object trouvé”: appropriation, ‘détournement’, subversion, etc.

From Dadaism to Surrealism, to Pop Art, and Situationism to Fluxus and Nouveau Realism and today’s post-modern Trash art and Found objects, we find here many enthralling issues and discourses, both aesthetic as well as socio-political. Trash art questions received aesthetic conventions.

Junk is a powerful medium that must be given an artistic design: Robert Rauschenberg, César, Ben, J.Beuys, David Hammons, Jimmie Durham…The boundary between trash art and found objects is not watertight.

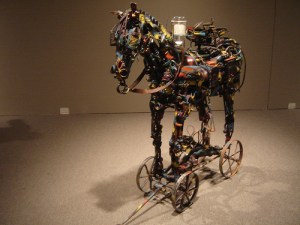

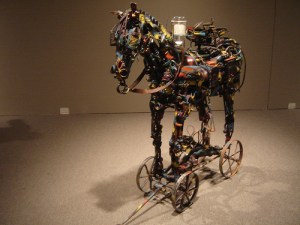

Kjartan Slettemark’s Cocaflower is trash, because an empty Coca Cola can is by definition empty packaging, in other words, trash, recyclable material. South African Willie Bester’s horrifying sculptures of recycled metals that depict cold uniformed giants riding ridiculous war machines are trash, because the objects used in the construction appear as junk. Benin artist Romuald Hazoumé’s African masks made of plastic containers and other garbage strike similar chords. Roddy Bell’s fans and frames are found objects because they are perceived as fans and frames. Safaa Erruas’ pillowcases and shoes are representations of found objects; Jon Gundersen’s briefcase with a pacifier is both a found object and trash, because it combines both. Vigdis Haugtrø and Jan Franciscus de Gier’s Europallets painted with rosemaling are modified found objects; Bill Morrison’s film clip compositions are found footage …

Work by Bester

Work by Hazoumé

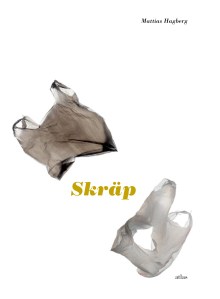

“Recycling the looking-glass” publication

(Recycling the Looking Glass-Trash Art-Found Object)

everydaytrash: How does trash art fit into the canon of accepted and appreciated media? What is the future of trash art?

M’kadmi : In our global art history, a history that is not yet written, Trash art is already an integrated genre. Trash, both as raw material and sign, has a major place in our global contemporary art. Many artworks made of trash are already canonised.

But, in spite of this canonisation Trash remains a “hot” matter because it often entails an implicit, if not explicit, critique of society. For the artist, trash is not solely signs, symptoms, markers, evidence and indicators of interpersonal experience and the various different existential foundations of all humans, but a signifying material for communication and expression.

Asking about the future of Trash art is like asking about our future relation to waste and all that is refused, denied, is in a way asking about our future relation to death.

Samir and Nasra at the opening

Susan Strasser’s bio describes her as “a historian of American consumer culture.” Her book, ‘Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash’ covers America’s tranisiton from a thrifty,resourceful culture to one whose definition of “trash” has vastly expanded.

Susan Strasser’s bio describes her as “a historian of American consumer culture.” Her book, ‘Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash’ covers America’s tranisiton from a thrifty,resourceful culture to one whose definition of “trash” has vastly expanded.

We end a fantastic week of trash author interviews with

We end a fantastic week of trash author interviews with  The latest issue of the hard-cover Canadian art magazine, Alphabet City, covers our very favorite topic. I came accross it at the Whitney last weekend and have been peering at the chapters one Subway ride at a time every since. What I like best about this book is how diverse it is, covering everything from really wonky articles to a woman’s poems about her sanitation worker uncle. It starts off with beautiful close-up photos of dust bunnies and covers everything from a collection of found paper airplanes to photos of industrial spaces to forgotten people in Mexico. I’ll try to hook up an interview with the editor.

The latest issue of the hard-cover Canadian art magazine, Alphabet City, covers our very favorite topic. I came accross it at the Whitney last weekend and have been peering at the chapters one Subway ride at a time every since. What I like best about this book is how diverse it is, covering everything from really wonky articles to a woman’s poems about her sanitation worker uncle. It starts off with beautiful close-up photos of dust bunnies and covers everything from a collection of found paper airplanes to photos of industrial spaces to forgotten people in Mexico. I’ll try to hook up an interview with the editor.